Ancestor of many modern breeds, the Soay sheep is a true living remains adapted to the harshest conditions!

If his name seems familiar to you it’s normal ; we have already featured him in a previous article.

The Soay sheep, a hardy and resistant breed that requires very little maintenance and nutritional contributions, is used (with the Ardennes spotted and the Ardenne Reds) as part of the “extensive grazing” action of the Life in Quarries project.

But, the story of this almost prehistoric breed, closest current relative of the now extinct bighorn sheep (mouflon in french), is so particular, that we couldn’t not tell you about it. Ready to learn more about these incredible mowers?

The Sheep Island

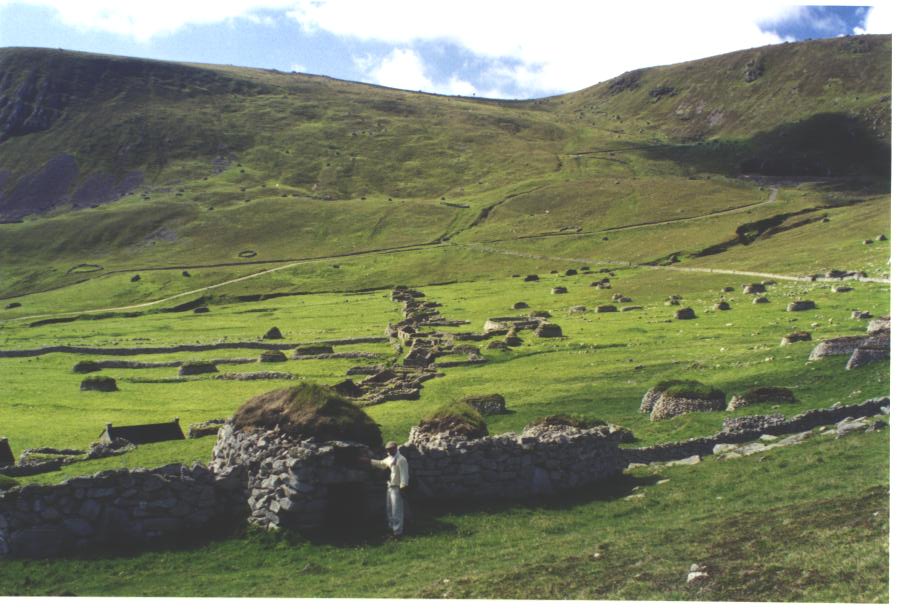

Our story begins in the archipelago of Saint Kilda located between Scotland and Iceland, on an island made up of green and gray moors dotted with rare shrubs and boulders torn thousands of years ago from the rocky slopes.

On this rocky pebbles of volcanic origin of 99 ha, located in the south of Greenland, no trees, no shelters.

Only the short plain swept by the wind, the rain (1100-1300 mm per year) and the cries of sea birds. The houses are made of stone, the earth is black, life is difficult.

It is here that about 1000 years ago, the Vikings (the last people to manage herds of wild sheep in Europe), stop over and drop off some domesticated animals in order to make this piece of land desert a game reserve.

In the process they baptized the island “So-ay”, literally, “sheep island”. Then, they set off again aboard their drakkars, abandoning the sheep to their harsh island life. Little by little, the archipelago made up of the Soay and Hirta islands is populated, but the geographical and climatic conditions make daily life a permanent struggle.

In 1727, the inhabitants living on Hirta were wiped out by smallpox. Of the last thirty survivors, the number rose to 100 and was maintained until the middle of the 19th century when most emigrated to milder skies.

In 1932, the last inhabitants of the archipelago demanded their evacuation in Scotland, leaving Hirta and Soay abandoned. A nature enthusiast, the Marquis de la Butte, then bought the archipelago with a view to making it a nature reserve. To do this, he made sure that no domestic animal was left on Hirta when the last islanders left and he then transfered a hundred sheep from the neighboring island of Soay.

After that … nothing. He ensured that no human intervention interferes with the natural development of life on the islands.

This is the reason why, while during the last two millennia, many breeds from the Near East have been introduced into European herds in order to create our “modern” sheep (more productive in terms of milk, meat and wool), the difficulties of access and the return to the wild state of the islands of Hirta and Soay made it possible to avoid the genetic hybridization of the breed and have allowed it to keep its appearance close to the bighorn sheep, the ancestor of all the sheep!

If you please, draw me a sheep.

Exit the little sheep with white wool that grows continuously !

Because, if during our industrialization past, the sheep has been perfectly adapted to the techniques of shearing, dyeing, spinning and weaving of wool, there long ago was a period when he was only used for its meat, its fat, its horns and bones.

In those remote times, it sports a dark-colored fleece made up of straight, stiff hairs (so-called “coarse jars”) that fall out every year. A fleece very similar to that of wild sheep, like the Soay sheep, a true remains of the Bronze Age, which has kept its prehistoric characteristics both in terms of the fibers of its fleece … and of its skeleton.

Thus, the Soay still has a fairly short tail today that sheds naturally annually, two techniques that allow it to avoid myasis (fly laying in old wool or soiled wool). But the Soays have also kept their “survival skill” since they are still not very demanding in terms of food (where a “modern” sheep supports 10 to 20% of woody plants in its diet, the Soay, although that it still needs grasses, supports them up to 60%), resistant to diseases and harsh climatic conditions thanks to their ancestral fleece and very resistant hooves. In addition, their conversion rate of plant biomass into energy is optimal, which makes them ideal for the maintenance of wasteland, natural spaces, parks and orchards.

Among the Soays, we are “territorial” from generation to generation. Indeed, the territory available for pasture is naturally divided into different zones, controlled by herds of 10 to 25 ewes from the same family. And as in human history, the best and oldest bloodlines are entitled to the best spots (at least until they run out and others take their place).

For the males, who live among themselves from January to October, the rutting season causes such energy expenditure that they often cannot replenish their fat reserves before the cold weather. Breeding rams are therefore the first victims of the rigors of winter. However, nature, if it seems cruel, is well done.

Because this situation allows the arrival of a new male the following year, thus reducing the risk of inbreeding.

And if, the Soays have kept their wild side (besides the rams as the ewes carry horns), this can pose a problem to the shepherds since the dogs prove to be effective when it comes to gathering the flock which is rather inclined, in the face of the threat, to scatter into sub-groups led by an experienced sheep.

A word of advice, therefore, plan an adequate system such as a containment corridor (more than a meter high to avoid playing leapfrog) in which you will get the herd used to passing without closing it. Thus, the day you have to collect them (identification, medical check-up, sorting, etc.) it will be done smoothly and much more easily.

Boys with boys

With a fierce (required in the wild) and territorial temperament, the Soay sheep are not suitable for intensive temporary maintenance by transhumance.

No, Soay sheep are more homeowners, which is why they are best suited for extensive permanent grazing systems (which may be combined with a rotation system). They are particularly suitable for managing the permanent maintenance of natural spaces, such as for example near Falaën (province of Namur), where a herd of ten Soay sheep are used to clear and maintain the old limestone meadows and slopes. wooded areas (2ha) at the foot of Montaigle. Or, as in the Polders, where for more than 20 years, more than 60 Soays sheep (spread over 4 herds) have maintained a private natural area of around 4 ha. Or, again, as is the case for the Clypot quarry (province of Hainaut), a member of the Life in Quarries project, where a herd of a few rams graze on the heights of the active site, managing to access the most set back from the field.

It is, moreover, good to specify that the Soay adapts very well to human activity and to other animals despite its instinctive caution.

However, if eco-grazing tempts you, know that to have Soay sheep (because these animals, gregarious, cannot live alone), you must have at least 30 ares for 2 ewe lambs, or 50 ares for 3 rams. And that mixing is not recommended unless you want to sort out the newcomers every year and attend great fights!

Favor unisex groups (rams or ewe lambs which have never reproduced before) as is, for example, the case for the maintenance of the ruins of Mariemont which, since 2012, 5 or 6 rams, or the maintenance of the old settling ponds of the Frasnes sugar refinery where 15 rams have grazed since 2008.

NB: By choosing rams (minimum 3) of the same age and from the same herd, fights for hierarchical rivalry will be significantly reduced.